Documentation Isn’t the Problem—Structure Is

Why rewriting documentation won’t fix a system that users can’t navigate

You can’t “write your way” out of an architecture problem. (I’ve watched teams try.) When documentation goes wrong, teams often assume the issue is writing quality. The reflex is “rewrite it,” “simplify it,” or “add a tutorial.” Sometimes that helps. But across enterprise and product environments, the consistent pattern is this:

Good writing fails inside bad architecture.

If the content can’t be found at the right time, in the right context, by the right audience, it doesn’t matter how well it’s written. That’s not a writing problem—it’s a findability and taxonomy problem.

Real-World Use Cases Where This Shows Up

Use Case 1: Onboarding documentation that no one follows

A new hire gets:

an onboarding doc

a folder of links

a handful of “start here” pages

The intent is good. The experience is not. Why? Because onboarding content is often organized by contributors (“HR,” “IT,” “Team”) rather than by user journey (“Day 1 setup,” “Week 1 workflows,” “How decisions get made here”).

That mismatch is classic HCI: users need progressive disclosure and clear wayfinding, not a dump of content.

Use Case 2: Incident response runbooks under pressure

Under stress, humans don’t “search”; they pattern-match. If your runbook structure requires interpretation, teams will improvise. The most useful runbooks:

have predictable structure

use consistent naming

include prerequisites

minimize branching

Human Factors 101: under time pressure, reduce cognitive load and decision points.

Use Case 3: Policy documents in regulated environments

Healthcare, finance, child protection programs, privacy/security—any area where compliance matters. People need to know:

what changed

what to do now

which version is authoritative

If those cues are missing, people stop trusting the system and default to local copies. That’s how “shadow policy” spreads.

Use Case 4: API docs and platform integrations

Most API doc sets contain multiple content types—reference, tutorials, conceptual explanations. Without clear entry points, users bounce:

“I need a quick example”

“I need to understand authentication”

“I need error handling guidance”

Good doc architecture makes these intent paths obvious.

The Architecture Behind “Documentation That Works”

In practice, effective documentation systems do three things:

Clarify intent (what is this page for?)

Clarify audience (who is it for?)

Clarify relationships (how does it connect to other content?)

This is where taxonomy becomes your best friend.

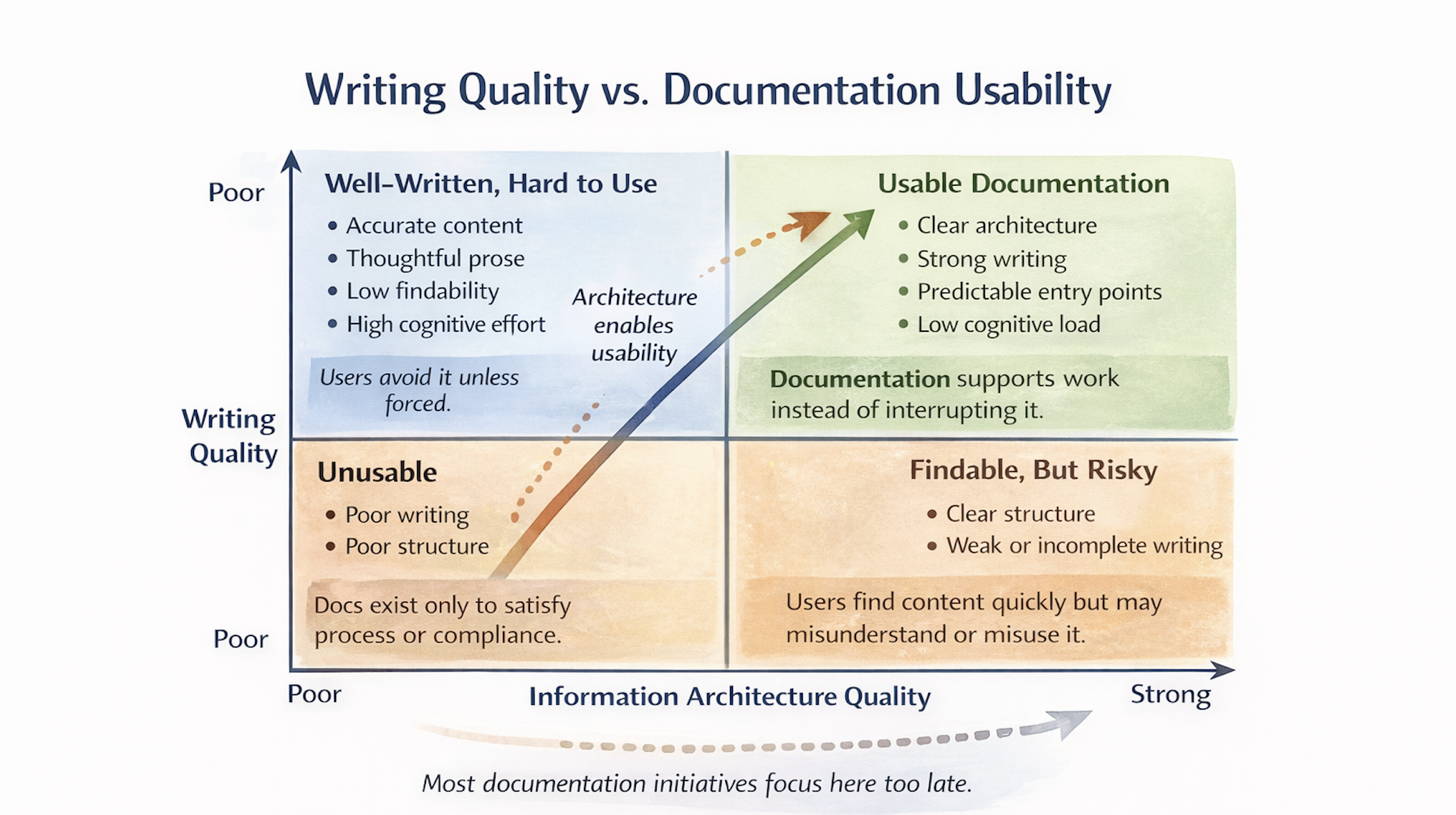

Writing Quality vs Documentation Visibility

Figure 1. Conceptual two-axis chart showing writing quality on the vertical axis and information architecture quality on the horizontal axis. The chart highlights four states of documentation: unusable, well-written but hard to use, findable but risky, and usable documentation. An upward diagonal arrow indicates that improving architecture enables usability even when writing quality is already strong.

Visual: Documentation Taxonomy Ladder (Build-Ready Diagram)

Diagram Title: Documentation Taxonomy Ladder

Format: A ladder with 5 rungs (bottom to top)

Domain (e.g., Security, Child Protection, Fundraising Ops, Product Platform)

Content Type (Policy / Procedure / How-to / Reference / Conceptual)

Audience (New hire / Operator / Admin / Developer / Leader)

Task (Onboard / Respond / Configure / Troubleshoot / Decide)

Artifact (the actual page)

Callout: “If you can’t classify it, users can’t predict it.”

This ladder makes taxonomy practical: it becomes an indexing system, not an academic exercise.

Practical Pattern: Content Types as Contracts

One of the highest-leverage moves you can make is to standardize content types with templates. The template is a contract:

Policy: purpose, scope, rules, owner, review cadence, change log

Procedure: prerequisites, steps, time estimates (if relevant), escalation paths

How-to: task goal, steps, success check

Reference: searchable facts, parameters, definitions

Conceptual: mental model, diagrams, constraints, examples

When content types blur, users lose trust. They don’t know what they’ll get when they click.

Real-World Failure Mode: “Everything is a How-To”

Many orgs collapse everything into “how-to” documents because it feels actionable. The result:

policies masquerade as steps

reference details are buried in prose

conceptual knowledge is missing

That’s how teams end up with “docs that exist” but don’t actually support thinking.

A Minimal Governance Model That Doesn’t Feel Like Governance

Governance fails when it’s heavy. It succeeds when it’s supportive.

Minimum viable governance:

Each domain has an owner

Each page has an owner + last reviewed date

New pages must select a content type + domain

Duplicates get merged or redirected (no silent forks)

This doesn’t slow teams down—it reduces rework.

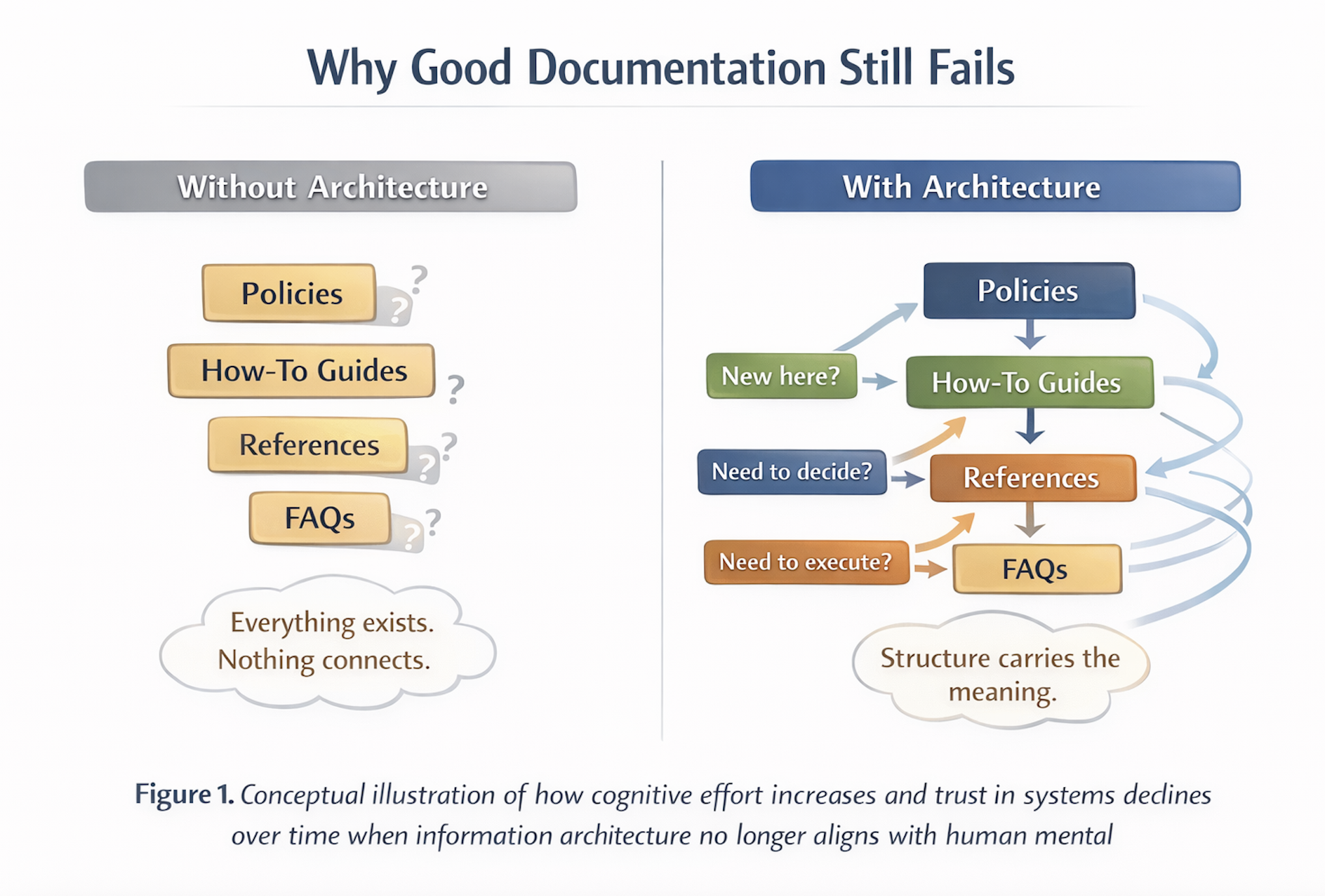

Visual: “Good Docs in Bad Structure” Comparison (Build-Ready)

Two-Panel Diagram

Figure 2. Conceptual comparison of documentation without information architecture versus documentation supported by clear structure. When content exists without defined relationships or entry points, users must interpret and guess. When architecture is present, structure guides intent, reduces cognitive load, and allows meaning to emerge through predictable pathways.

Two-Panel Diagram Explained

Left: “Great writing, unclear structure”

multiple entry points

inconsistent labels

no owner/lifecycle cues

Right: “Good writing, clear structure”

one domain front door

consistent content types

clear lifecycle cues

Caption: “Writing quality helps comprehension. Structure enables use.”

Final Thoughts

Documentation is not just communication. In many organizations, documentation is the operating system for work. If its architecture is unclear, teams compensate with meetings, Slack threads, and heroics. The goal is not “more documentation.” The goal is less confusion.

References (Foundational):

Redish, Letting Go of the Words (content that supports tasks and scanning): https://redish.net/books/letting-go-of-the-words/ (Redish)

Rosenfeld/Morville/Arango, Information Architecture (classification, navigation, governance): https://books.google.com/books/about/Information_Architecture.html?id=dZaJCgAAQBAJ (Google Books)

Write the Docs (community practice and doc patterns): https://www.writethedocs.org/guide/index.html (Write the Docs)